Delightful Cheese…

What more needs to be said? With a different cheese to satisfy every palate, the options are endless: creamy brie, soft and smooth; blue cheese, sharp and salty; Parmigiano-Reggiano, sprinkled over pasta; sharp cheddar, nestled inside a grilled-cheese sandwich; and the list goes on.

Found in every part of the world, cheese is one of the world’s most basic, yet most nutritious and flavourful foods. A skill of domestic origin, cheese-making became an art, which has in turn become the global cheese industry. The successful marriage of art and industry has resulted in the production of high-quality cheeses that are durable, have the ability to be produced on a large scale, and are transportable across continents and oceans without significant loss of their original character.

Are microbes in cheese safe?

Cheesemaking is intricately linked to microbiology and the microbiological safety of cheese is a topic of renewed interest as global demand for cheese and cheese products continues to grow (Donnelly, 2014). The availability of artisan cheeses has created a renewed interest in cheese making and cheese consumption among consumers. As the market for artisan cheeses grows, cheesemakers must ensure that cheese is safe and that there is an active adaptation of traditional recipes and methods to meet present-day regulations.

Cheesemakers in Canada and the United States are allowed to produce and sell cheese that has been made from raw milk as long as it has been aged for a minimum of 60 days at a temperature of not less than 2 degrees Celsius; the other option is to use pasteurized milk. Despite this regulation, and the fact that many countries consider traditional cheese made with raw milk to be a microbiologically safe product, governments in North America are considering requiring mandatory pasteurization of all milk intended for cheese production (Donnelly, 2014).

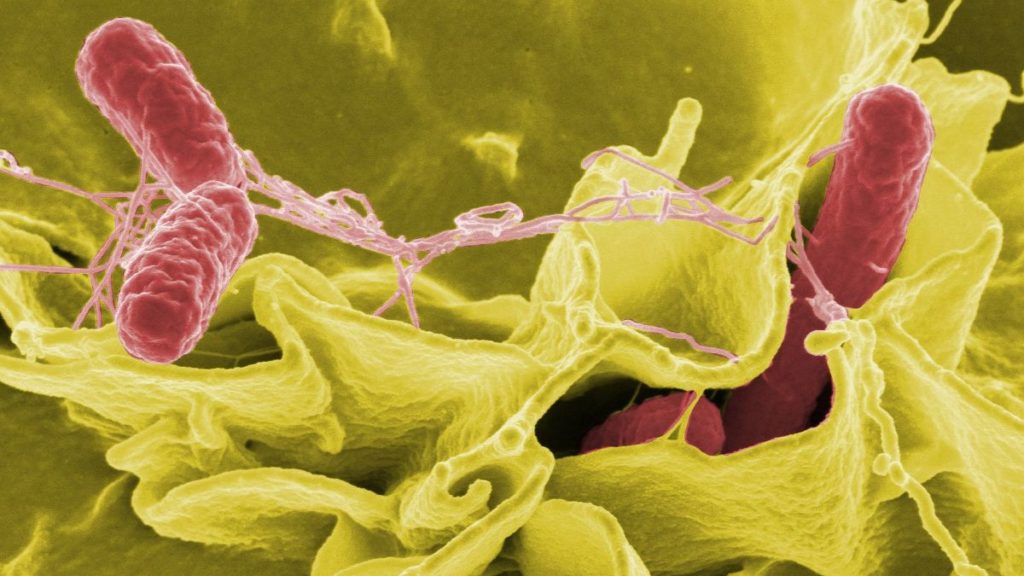

The pathogens of public concern during cheesemaking include E. coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enteric serovar Typhimurium DT104, and Staphylococcus aureus, and research has shown that they can survive much longer than the 60-day holding period (Donnelly, 2014).

Is cheese healthy?

The fact that cheese is delicious may seem like reason enough to consume it regularly; however, if your intellect needs convincing, the science is compelling. Cheese is a probiotic food: nowhere in the microbial world are microorganisms on more magnificent display than on the surfaces or in the interiors of the great cheeses of the world (Donnelly, 2014). Some might cringe at the thought of their favourite cheese being covered in tiny microorganisms, but it’s a reality that cannot and should not be ignored.

Many types of cheese are replete with probiotics, which according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization, are “live microorganism that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.” Probiotics improve the balance of microbiota in the intestines, improve mucosal defenses against pathogens (Boylsten, 2004), and have many beneficial health effects, such as: antimicrobial activity, relief in the symptoms resulting from lactose intolerance, antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic activities, stimulation of the immunological system, and improvement of urogenital health (Bomba, 2007; Shah, 2007). They have also been recommended for the treatment of conditions such as pseudomembranous colitis, chronic liver disease, and food allergies (Boyle & Tang, 2006).

Furthermore, cheese is a viable alternative to fermented milks, such as kefir and yogurt, as a food vehicle for the delivery of probiotics. For example, studies have shown that probiotic fresh cheese (Argentinian fresh cheese) which contained L. acidophilus A9, bifidum A12 and L. paracasei A13, increased phagocytic activity in the small intestine of peritoneal macrophages and demonstrated immunomodulating capacity in mice (Medici, Vinderola, & Perdigon, 2004). Cheese creates a buffer against the highly acidic environment in the gastrointestinal tract, and thus creates a more favourable environment for probiotic survival throughout the gastric transit, due to higher pH. Moreover, the dense matrix and relatively high fat content of cheese may offer additional protection to probiotic bacteria in the stomach. (Gomez da Cruz, 2009)

Are there technological hurdles to producing stable probiotic cheese?

The major challenge associated with the application of probiotic cultures in the development of functional foods is their viability maintenance during processing (Gomez da Cruz, 2009). First and foremost, probiotics must be able to survive standard dairy processing; technological suitability is also important in microorganism selection, so that probiotics are able to maintain viability and efficacy throughout consumption and in the food product on a commercial scale. Probiotics must to be able to multiply and survive at elevated levels in cheeses for the duration of their shelf-life and chosen strains must be suitable for large-scale industrial production (Stanton et al., 2003).

We only use best-in-class instruments, predictive modeling tools and statistical analysis to ensure your process and product/s meet the requirements of the new regulations. Our dairy expertise includes, but it is not limited to:

- Development and implementation of any GFSI scheme;

- Heat-treated less than pasteurized (federal);

- HTST dairy processing (federal level).

Call us for a free consultation. Direct line (+001) 647-963-0182

Resources:

Bomba, A., Nemcova´, R., Mudronova´, D., & Guba, P. (2002). The possibilities of potentiating the efficacy of probiotics. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 13(4), 121e126

Boyle, R. J., & Tang, M. L. K. (2006). The role of probiotics in the management of allergic disease. Clinical and Experimental Allergy, 36(5), 568e576

Boylston, T. D., Vinderola, C. G., Ghoddusi, H. B., & Reinheimer, J. A. (2004). Incorporation of bifidobacteria into cheeses: challenges and rewards. International Dairy Journal, 14, 375e387.

Donnelly, Catherine W. Cheese and Microbes. 2014. ASM Press, 2014.

Gomez da Cruz, Adriano, et al. “Probiotic cheese: health benefits, technological and stability aspects.”Trends in Food Science & Technology. 20 (2009) 344-354.

Shah, N. P. (1997). Bifidobacteria: characteristics and potential for application in fermented dairy products. Milchwissenschaft, 52(1), 16e20.